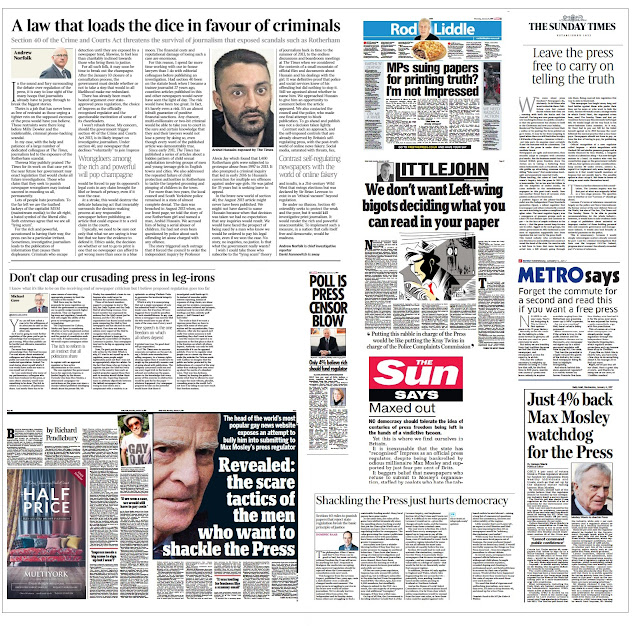

Newspaper readers have been bombarded this week with dire warnings about how the Government, the Left, a gaggle of press-hating fanatics, celebs and vindictive tycoons want to censor what they read. Reporters, leader writers and columnists on both national and local titles have been called to arms to hammer home the argument.

Their articles take a similar approach: "This is really boring and you may not think it matters, but it's important for YOU." So important that the Metro published its first leader in 17 years to make the case.

Meanwhile on social media and in the blogosphere there has been a similar flurry of activity, denouncing the lawless, lying Press and its scare-mongering.

Newspapers say they face the toughest regulation in the world, critics that our Press is one of the least trusted in the world.

What has got everyone hot under the collar? Press regulation.

But didn't we go through all this a few months back? Yes.

Last October a putative regulator called Impress gained recognition under the Royal Charter set up after Leveson. That raised the prospect of implementation of Section 40 of the Crime and Courts Act - which could not apply until there was an approved regulator - and the first bout of "beware the enemies of Press freedom" editorials.

Rather than enforce Section 40 (details soon), Culture Secretary Karen Bradley announced a public consultation on the subject and on whether the second part of the Leveson inquiry - looking into the relationship between the Press and the police - should go ahead. That consultation period ends on Tuesday, hence the latest clamour.

Rather like the EU referendum campaign (there are other similarities, not least David Cameron opening a can of worms to help him wriggle out of a sticky situation), the arguments put forward are partisan and incomplete. Both sides of the debate claim that their preferred regulator is independent and that the rival one is beholden to a vested interest. Both sides have published opinion polls that apparently show public support for their case. One side says the freedom of the Press is in danger, the other that it is being protected. The newspapers have bandied Max Mosley's name around a lot, although he is actually a red herring.

SubScribe has written about regulation on several occasions, most frequently in 2013 in the aftermath of Leveson, when the whole Royal Charter debate started. Looking back at the posts, I would change a few things - not least some of the language - but today I want to try to set out the background and examine some of the claims and counter-claims. As all our columnists say, it's likely to be tough going for the reader, but I hope it will be worth it.

Leveson

Sir Brian Leveson's inquiry concluded that a new system of "independent self-regulation" was required for the Press that would protect the interests of the public and govern the industry. Since newspaper misconduct had been the subject of seven official inquiries in as many decades, Leveson felt that legislation was needed to underpin the establishment of the new body (or bodies).It was not, he said, for the Government or Parliament to set up such a body; that should be down to the Press. The new regulator should operate independently of government and of the newspapers it oversaw and have no influence in the publication or suppression of anything other than corrections. Parliament's role would be to accept a duty to protect the freedom of the Press and to establish a process by which the new body would be officially recognised.

The report went on to list 47 recommendations on the form and function of the new regulator.

The Royal Charter

Parliament accepted most of Leveson's recommendations and decided to create a Royal Charter to establish a Press Recognition Panel, which would determine whether any regulator that came forward complied with the Leveson criteria. The shape of the Royal Charter was agreed by the three main party leaders and put to representatives of the lobby group Hacked Off in an early-hours meeting in Westminster. No representatives of the newspaper industry were in attendance.The industry meanwhile dismantled the discredited Press Complaints Commission and established the Independent Press Standards Organisation, under the chairmanship of the former Appeal Court judge Sir Alan Moses. Most national and local newspapers, with the exception of the Guardian, i and Financial Times, have signed up to be regulated by Ipso. It has not sought recognition under the Royal Charter.

A second regulator, Impress, was set up independently of the industry with £3.8m of financial backing from Max Mosley plus crowd-funded donations, including contributions from JK Rowling and David Sainsbury. Up to 50 (reported numbers vary) mostly local organisations have signed up to be regulated by Impress and it was given official recognition in October.

The Royal Charter was brought into being through two acts of Parliament, one of them the Crime and Courts Act 2013. It is this law whose Section 40 is the subject of the current angst. This seeks to encourage newspapers to sign up to a recognised regulator by offering a level of protection against vexatious litigation, while also making redress more accessible for people without deep pockets who have been wronged by the Press.

In order to achieve recognition, a regulator has to offer people with legal complaints (such as libel or invasion of privacy) against a newspaper an affordable arbitration service to avoid racking up expensive court costs. Under Section 40, any complainant - or newspaper - who insists on going to court when they could have used arbitration must expect to foot the entire legal bill, regardless of the outcome.

The rival regulators

Leveson provided a template for how a regulator's board should be appointed, who should be qualified to serve, how it should conduct itself and so forth.He suggested the chairman and board should be appointed by panel with a substantial majority of members of people "demonstrably" independent of the Press, at least one person with a current understanding/experience of the Press, and no more than one serving editor.

The board itself should also have a majority of people independent of the Press, a "sufficient" number of people with experience of the industry, including former editors, senior or academic journalists, but no serving editors or MPs.

The Ipso board has 12 members. Five, including the chairman Sir Alan Moses, have no discernible connection with the Press, two others are mostly involved with television, three are former newspaper editors, one is a serving magazine editor and one a national newspaper executive.

Its 12-strong complaints committee comprises eight journalists, a solicitor, two with knowledge of dealing with disputes involving the NHS or financial services, and Sir Alan.

The Impress board has eight members under the chairmanship of Walter Merricks, a former financial services ombudsman. Three are journalists, though none now works for a newspaper, another is the chief executive of Action on Smoking and Health, one an insurer and two practise media law.

In the sticks-and-stones world, those who deride Ipso point to the fact that Trevor Kavanagh of the Sun serves on its board, while those mocking Impress point their fingers at Martin Hickman, the former Independent journalist who co-wrote Dial M for Murdoch about the death of a private investigator linked to the News of the World.

Ipso is criticised for having "too many" journalists on board, Impress for having too few.

Newspapers knocking Impress also make great play of its financial dependence on Mosley, who won a libel action against the News of the World after it accused him of involvement in a "sick Nazi orgy" with five prostitutes. The court ruled that there was no Nazi element to the goings-on.

Critics of Ipso say it cannot be independent because it is funded by the newspapers it regulates. It was, however, Leveson's expectation that the Press should finance its own regulation and Impress hopes that fees paid by papers that sign up will eventually fund its operations.

Both organisations insist that their boards operate entirely independently of the bodies that finance them. Mosley's money is funneled through a charitable trust and cannot be withdrawn other than in exceptional circumstances - such as Impress going bankrupt. Ipso's money comes through a funding company whose board is entirely made up of industry representatives. It says that its independence is guaranteed because of the lay majority on its board.

Supporters of Impress cite a YouGov poll commissioned by Hacked Off showing that 73% of people believe that newspapers should be regulated by a body independent of government and publishers, with only 3% supporting a regulator set up by publishers. Newspapers counter with another YouGov poll, this time commissioned by the News Media Association, showing that 49% of respondents thought the Press should finance their own regulation with only 4% thinking wealthy individuals should foot the bill. Given the phrasing of the questions, both sets of responses were entirely predictable - as was the fact that each camp accused the other of misinterpreting the results.

One "external" assessment of Ipso says it's doing an OK job, another that it's a disaster.

Both regulators offer a "low-cost arbitration"service, although Ipso's is only a 12-month pilot project. The Impress system, which uses a firm of commercial arbitrators, is free for complainants. The website says that an administration fee is payable, but complaints chief Brigit Morris told SubScribe that plans to charge £75 had been abandoned at least for the time being. Ipso charges £300 plus VAT for basic arbitration and if the complainant wants a further ruling, they have to pay a maximum of £2,800 plus VAT. Both expect the publisher to pay the cost of the arbitrator and for each side to pay their own legal fees. Both discourage the incursion of such fees, emphasising that the intention is to create a lawyer-free zone.

The consultation

The Government is asking people whether Section 40 should be implemented, repealed, put on hold or implemented in part - allowing papers signed up to Impress to benefit from the costs protection without penalising those outside the regime. Responses are invited in the form of a questionnaire and Private Eye has helpfully tweeted the link, which is reproduced here.Campaigners have been even more helpful. Hacked Off has produced a template response, which you can see here, and also published a critique of a rival template published on a site called freethepress.co.uk.

Hacked Off notes, correctly, that the template is the only content on the freethepress site and that it gives no details of members of supporters. Yet the group asserts that it was set up by "the Trotskyists-turned-libertarians of Spiked magazine" and "appears to be financed by the newspapers". It may mean the hashtag Twitter campaign and possibly material on the News Media Association site, but that's not what it says.

What does SubScribe think?

Ipso got off to a promising start, but seems to have stalled. It needs to make sure it is Leveson-compliant, fine-tune its arbitration service and generally shape up so that it can secure at least the support of the unregulated Guardian, FT and i. The failure to do that speaks volumes.It also needs to be more pro-active in initiating investigations; it was too slow off the mark during the EU referendum campaign where newspapers knew that they could write whatever they liked and that there would be no time for them to be forced into correcting misleading material before the vote. It should be more robust in enforcing the Editors' Code provisions for separating news reporting and comment and be bolder in demanding prominent corrections - it is unfathomable that it is still seen as acceptable to publish a lie in 120pt on page one and a correction in 8pt on page 2.

There are signs of hope in that Paul Dacre has at last stood down as chairman of the Code committee (of course, levels of joy about that depend on who replaces him) and that Moses has shown a willingness to engage with groups of people who want to discuss various issues with him. That hope is, however, dampened by an interview with the FT in which he said that much of what he saw in the papers -about immigration in particular - dismayed him, but that he was not in a position to do much about it.

Faith in Ipso was certainly dented with the rulings on Katie Hopkins's "cockroaches" piece and Kelvin MacKenzie's tasteless remarks about the newsreader Fatima Manji. Tony Gallagher's defiance after being forced into a correction on the Queen and Brexit and Trevor Kavanagh's crowing over the Manji ruling did not help.

The question is, would another regulator have ruled against Hopkins or MacKenzie? Obnoxious as their words were, they were expressing personal opinions and we have no right not to be offended. SubScribe readers will know that this blog finds much coverage of migration offensive and disproportionate, but where it is true, readers are the only people who can stop it - by not buying. No regulator can dictate news values or impose punishments because they think an article is in bad taste.

As to Impress, it never had a chance of attracting the support of any significant newspaper. Mosley's involvement is an irrelevance - a bit of colour for the Littlejohns and Liddles, an opportunity for the Sun to give us all a laugh with a leader saying we can't entrust our free Press to a vindictive tycoon. (Of course it wasn't irony fail, as Twitter chortled. It could only have been deliberate.)

As Sun editor Tony Gallagher said in his interview on Radio 4's Today programme this week: "No newspaper worth its salt will sign up." Not because of Mosley, but because newspapers are resolute about having no truck with any State-approved regulator, no matter how many checks, balances, promises and pledges are made about political interference. Impress could have been set up by the Angel Gabriel, financed by the most benign benefactor and staffed by legendary journalists and the greatest brains of the age. The answer would still have been No.

[Incidentally, Gallagher was given a rough ride for asserting in his Today interview that Leveson had cost £50m. It didn't. It cost about £5m, and Sarah Montague put him right. The inquiry, the police investigations and the court cases cost £43m - but none of those would have happened if Gallagher's sister paper hadn't broken the law and his employers handed over masses of material betraying staff and sources alike. That apart, it was game of him to agree to appear at all; tabloid editors do not generally submit to interview.]

And so to Section 40. Leveson recognised that newspapers would need to be cajoled into accepting a regulator approved by the State, so he suggested introducing a penalty for unregulated papers that ended up in court rather than use a cheap arbitration service. His idea was that they should not have their own costs reimbursed by the litigant, even if they won:

The normal rule is that the loser pays the legal costs incurred by the winner but costs recovered are never all the costs incurred and litigation is expensive not only for the loser but frequently for the winner as well. If, by declining to be a part of a regulatory system, a publisher has deprived a claimant of access to a quick, fair, low cost arbitration of the type I have proposed, the Civil Procedure Rules (governing civil litigation) could permit the court to deprive that publisher of its costs of litigation in privacy, defamation and other media cases, even if it had been successful. After all, its success could have been achieved far more cheaply for everyone.

If MPs had followed that advice, we might not be in the middle of this furore. But they took it a stage further and decided that, win or lose,

whichever party had shunned arbitration should pay both sets of costs. Section 40 states (on page 45 of this link):

If the defendant was not a member of an approved regulator at the time when the claim was commenced (but would have been able to be a member at that time and it would have been reasonable in the circumstances for the defendant to have been a member at that time), the court must award costs against the defendant unless satisfied that (a) the issues raised by the claim could not have been resolved by using an arbitration scheme of the approved regulator (had the defendant been a member), or (b) it is just and equitable in all the circumstances of the case to make a different award of costs or make no award of costs.

[The Act's previous paragraph makes the same provision in reverse for claimants who could have used an arbitration service, in an apparent attempt to offer a carrot as well as a stick to newspapers to sign up.]

The potential for abuse is obvious. Anyone could attempt to deflect any investigation of their activities by threatening to sue, knowing that they could hire the costliest lawyers in the land and not have to pay the bill. A provision that was supposed to encourage compliance with a regulatory regime and provide cheap redress for ordinary people was turned into a potential weapon for the wealthy, powerful, corrupt and criminal.

Newspapers that don't want to be regulated by anyone authorised by the State - let alone Max Mosley and Hacked Off - felt that they were being blackmailed into submission.

The language may be melodramatic, hysterical even. If you want to see threats to Press freedom, look at Turkey, at Egypt. Read the Committee to Protect Journalists or Reporters Sans Frontieres websites. To say, as many papers do, that Britain has the toughest system of Press regulation in the world is patent nonsense. Yes, Ipso has the power to fine miscreants up to £1 million, but I am not aware of any financial penalty being imposed on any publication (I may be wrong).

Had MPs enacted the Leveson recommendation, newspapers would still have squealed, but their case would have been weaker. They might lose money defending a winning case, but at least they would be in a position to make a decision about how much they were willing to risk in the fight. If they have to pay the other side's legal bill as well, there is no knowing where it could end.

As it stands, Section 40 offends natural justice, and it is this fact that adds power - and some public sympathy - to their argument.

SubScribe suspects that courts would recognise that, and that judges would reject the costs directive in favour of the (b) provision that it would not be just or equitable. But the very existence of Section 40 would leave papers vulnerable and local journalists, in particular, could be scared off tricky investigations. The protection against vexatious litigants wouldn't be enough to overcome the risk of bankruptcy if a case ended up in court.

So just sign up? Well here the Mosley factor comes back into play. Even if papers put aside their qualms about state-backed regulation, most would balk at being regulated by an organisation funded by Mosley and supported by Hacked Off - although the NUJ does support Impress.

What if Ipso applied for recognition? That would be the simplest solution. It would need to beef up its act - which it ought to do anyway - but that aversion to being tied to anything with any State involvement is still insurmountable.

Where next then? SubScribe's instinct is that Bradley will introduce the costs incentives for Impress publications without the penalties for the rest. To repeal Section 40 would show bad faith to victims of the excesses of the Press - and invite still worse behaviour from the worst of the newspapers.

There might be some value in leaving it on the books and offering abolition as a carrot if an unrecognised Ipso can demonstrate its independence and the effectiveness of its arbitration system.

But to enforce it and antagonise Murdoch and Dacre when Theresa May's Government needs all the help it can get in this pre-Brexit world? She'd be bonkers.

And isn't that where we came in - disquiet over newspapers' political influence and journalists' cosiness with politicians?

Further reading:

On SubScribe:

Elsewhere:

Tim Fenton, Zelo Street: Free speech campaigners busted

The Spectator, Tanya Gold: If you want more Katie Hopkins, campaigning for press regulation is the way to go

Hacked Off, Brian Cathcart: Four-part response to the consultation

David Higgerson: local papers will die if those who claim to champion a free press get their way

The Press Recognition Panel letter to Bradley

Newspapers all over the country: a comprehensive set of links to articles published since the consultation started can be seen on the Press Gazette website (there are a lot expressing the same view)

If you have read something that deserves to be added to this list, please comment and add the link, thank you.

As you point out, most of this arcane imbroglio IS boring for most readers, most of whom are their own regulators: if they don't like it they will a) stop buying the print version, b) ignore the free online clickbait, which too much of it is, and c) unsubscribe, ditto.

ReplyDeletePerhaps it's time that influencers and opinion formers such as you and Press Gazette focused on an issue which is perhaps even more critical for the future of the Press: plunging editorial standards, re both subject matter and writing style, ie, standards of grammar, syntax and basic comprehension, as well as factual accuracy.

For how much longer can the race to the bottom go on? Even the sacred Guardian is getting more and more online stick for its general bias and magisterial disregard and seeming disdain for Mr and Mrs Everyday Normal Middle-Of-The-Road Brit.

Odd isn't it that the press support this politicisation of the implementation of the Leveson reforms. The press are normally howling about any possibility that politicians step foot in what they see as their bailiwick. The Government and Karen Bradley are successfully undermining the carefully gathered evidence of a cross-party supported judicial inquiry. A politician, subject to the very real pressures of the press is to make decisions that cannot have the legitimacy of either the Inquiry or its recommendations.

ReplyDelete