Gareth Davies worked for the Croydon Advertiser for eight years, during which time he frequently made the news himself - as four-time winner of the weekly newspaper reporter of the year title and as the subject of a harassment order as he pursued the story of a conwoman who was subsequently jailed.

Gareth Davies worked for the Croydon Advertiser for eight years, during which time he frequently made the news himself - as four-time winner of the weekly newspaper reporter of the year title and as the subject of a harassment order as he pursued the story of a conwoman who was subsequently jailed.

Last week he provoked a Twitter storm with his tweets about the state of the paper he left in June. He has now put those thoughts into a detailed article, published below.

SubScribe's view of the latest debate and state of our local journalism can be seen here, here, here and here.

As Davies explains, Trinity Mirror has yet to comment on his thoughts as set out below. Further efforts are being made to encourage a response and SubScribe will happily publish an alternative view if one is forthcoming.

On Friday evening I tweeted a photograph of this week’s Croydon Advertiser, the first edition in the weekly newspaper’s 147-year history put together without the input of the reporters who wrote the stories and with minimal involvement of an editor. Instead the paper was made up of articles taken directly from the Advertiser’s website by sub-editors based 50 miles away in Chelmsford, Essex. This is what Trinity Mirror, which bought the paper in October 2015 as part of its purchase of Local World, calls Newsroom 3.1, which is designed to free journalists to concentrate entirely on generating web traffic.

This week’s paper is a mess. Little to no thought has gone into its design. The story count is low and photographs have been used far beyond their usual size in order to compensate. The image I tweeted was of two consecutive pages which, instead of local news stories, consisted of a pair of listicles: “13 things you will know if you are a Southern rail passenger” and “9 things you didn’t know about Blockbuster”. Both were clickbait written for the web and thrown into print to fill space - an indication of what the paper will be as a result of what Trinity Mirror calls a “truly digitally-led” newsroom.

As a strong believer in the value of local journalism, and having worked at the Advertiser for almost eight years, I felt people ought to know.

The tweets (you can find a helpful summary of them here) prompted a large response, receiving 400,000 impressions within 24 hours. People from outside the industry, including readers in Croydon, were surprised and disappointed. Many former reporters said they had left local journalism for similar reasons. I was also contacted privately by journalists at other local and regional papers who recognised an all too familiar tale but, knowing the likely repercussions, have been unable to speak openly about their experiences.

The Advertiser and the other papers in its newsgroup are far from the only newspapers trapped in this race to the bottom. Equally, Trinity Mirror is by no means the only publisher helping it along. It’s probably not even the worst offender.

But what is happening at my former paper is indicative of a wider problem undermining local journalism - and by that I mean what it should be and not what it has become - to such an extent that it is probably beyond saving, at least in its traditional form. This article is about Trinity Mirror, and before that Local World and Northcliffe Media, but many of the problems it describes are playing out in dozens, if not hundreds, of newsrooms across the country.

Redundancy call on the school run

On May 26 the new editor-in-chief of Trinity Mirror south east, Ceri Gould, read out a short statement to staff at five papers - the Croydon Advertiser, Crawley News, East Grinstead Courier & Observer, Surrey Mirror and the Dorking Advertiser - announcing a restructure in preparation for the switch to Newsroom 3.1 (papers in Kent and Essex had been given the news earlier in the day). Everyone was told that their current job no longer existed and that if they wanted to continue to work for the company, they would have to apply for new roles. The announcement met with stunned silence.We had known something was coming but, perhaps naively, not that. In a meeting later that day, reporters were told they would no longer have any role in putting together the newspapers they had worked for. Even the editor of the newly monikered “brand” would only have an “input” on pages one, three and five.

Our sole focus would be on writing stories for the website and, as a result, we would have to go “cold turkey” on the paper. A reporter, who has since left, asked whether we would still have the time to meet contacts. The newsroom, she was told, would become “much more like a daily paper”, meaning that reporters would be “tied to their desks”.

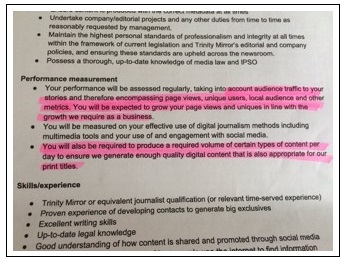

The pack provided at the start of the 30-day consultation process included descriptions for each of the new roles. Mostly they described things we already did, but with a rebranding - such as creating “total content packages”, focusing on “digital engagement” and generating “audience reach”. A section labelled “Performance measurement” said that reporters would have to produce a “a required volume of certain types of content per day” - ie quotas - and would be “assessed regularly, taking into account audience traffic to your stories and therefore encompassing page views, unique users, local audience and other metrics”.

This last point was particularly alarming, given that Trinity had dropped a previous attempt to introduce web traffic targets for reporters at the beginning of the year after the Daily Post, the Liverpool Echo, Birmingham Post, Newcastle Chronicle and Manchester Evening News held strike ballots in protest.

I asked to leave because I believe Newsroom 3.1 is the beginning of the end of the Advertiser as a newspaper. I’ve seen the impact of similar changes at Newsquest papers in south London and want no part of it. I would have found it very difficult to have no input into something I had spent eight years of my life working on. Story quotas and judging reporters by web stats are barriers to producing good journalism, especially when imposed on understaffed and under-resourced papers. Taking voluntary redundancy allowed me to look after my young son but, even if that were not a factor, redundancy would have been my only choice.

I raised these concerns with Ceri Gould. My fear about the future of the newspaper met with no response but I was told there were no plans to introduce quotas or to measure reporters by page views. When I pointed out both policies were in the job descriptions we had been given, she said the documents were out of date, and that I should take it on trust that it wasn’t going to happen.

I was assured that Newsroom 3.1 would provide opportunities for talented journalists, even those sceptical about its merits. Ceri cited Martin Shipton, the Western Mail’s veteran chief reporter, who, she said, originally hated the idea but had since become an enthusiastic convert. He told BBC Wales in June that Trinity Mirror was “anti-politics” and had convinced itself that the public was “more interested in lifestyle type journalism…than about important decisions taken about their lives”.

At the end of the meeting I was told my request for redundancy would be accepted. The box explaining why read “personal reasons, disagrees with Newsroom 3.1, no appetite”

Three others in our group, including a news editor and a senior reporter with a combined experience of more than 20 years, also decided to leave. Only one had a job to go to. Three more journalists have left since then. That leaves six reporters, all trainees, to cover Croydon, Sussex and Surrey (rather than working for individual papers as they previously did), as well as far wider areas.

“Please think beyond our traditional patches,” says a guide provided to staff last month by an editor. “Big stories from Sutton, Bromley, Streatham and Caterham do very well for Croydon. Big stories from Horsham, Brighton, Haywards Heath and Horley do well for Crawley. For Surrey any big stories from across the whole county can do well.

"And, for things like travel, days out or really huge stories (such as the Shoreham Air Show disaster) people can be very interested in things well outside our patch.”

Even under the old way of working, these reporters, like so many across the country, had seen the opportunity to cover important matters of public interest - court cases, inquests, employment tribunals, council meetings - severely restricted.

Now this inexperienced team of six trainees covers a population of approximately 3.5 million, with each area having guaranteed access to a photographer on only one day a week. They are overseen by five news editors, two of whom have been promoted but are, I am told, still paid the same as when they were reporters. Trinity Mirror is looking to recruit three journalists but, as the adverts say the positions will be in Croydon, Kent or Essex, it is unclear how many of the staff who have left will be replaced.

(At the end of the consultation process all the newsgroup’s editorial assistants - whose responsibilities varied from managing the photographic diary to writing community news - were made redundant overnight. One day they were at their desks, the next they were not. One, after 16 years' service, was told that she had lost her job over the phone while on a school run.)

Writing for five websites, covering areas we don't know

Reporters who applied for jobs were told they would be working shifts covering all areas in the newsgroup, which had not been mentioned during the application process. Instead of working 9am to 5.30pm, Monday to Friday, reporters now work shifts, the earliest of which begins at 6.30am and the latest finishes at 10pm on a weekday. Instead of each paper having one person on call at the weekend, who (at least theoretically) was allowed to claim a day back during the week, reporters now work both Saturday and Sunday on a rota. Employment law in England and Wales states that a person cannot be made to work on Sundays unless they and their employer agree and put it in writing. No such change to reporters’ contract has been suggested or agreed.Working in shifts with a reduced number of staff means that, once every six weeks or so, reporters will have to work 12 days in a row (including, for some, finishing at 10pm on a Friday ahead of an 8.30am weekend shift the next day). When reporters are on shift during the week and then at the weekend they will have worked 59.5 hours in seven days. The legal limit is an average of 48 hours over a period 17 weeks. One reporter has calculated that, under the new system, he will earn 50p less than the London Living Wage of £9.40 per hour. When I began as a trainee reporter in 2008 I was paid £14,500. The starting salary has not improved significantly since.

Staff were told that working in shifts was the only way to make Newsroom 3.1 work with the number of staff available. It was sold to them as ending the exploitative system that meant they regularly worked well beyond their contracted hours without extra pay or time back in lieu. Yet even under the new system they are expected to work outside their allotted shifts.

The guide says: “I would hope everyone already does this, but please if you spot a huge story out of hours take personal responsibility for ensuring we get it online with the same speed and quality as we would do if it was within working hours.”

Staff, who work in an office with no union representation, feel misled.

“The change has been tough - uncertainty always is - but what I think has been the toughest is becoming a reporter for all three patches,” said a source. “During the consultation we were not told that was a possibility. In fact we were advised to pick what patch we would like to cover when listing what roles we would wanted to fill.

“Then, after our interviews, the roles had changed and we were now expected to write for five websites, covering areas most of us had no experience of. That came as a shock. It’s worrying that we have not been given the chance to sign a new contract as a result of these changes, especially with the new hours we are working.

“The new way of working has improved the way we cover breaking news, but the hardest thing is how under-resourced we are. I’m holding out hope that more reporters will mean more time to work on public interest stories rather than listicles designed only to get hits.”

Reporters are concerned that covering huge areas with significantly fewer resources will affect their ability to produce good journalism.

Thankfully, the guide finishes with a helpful reminder.

While we are working different hours and in a different way, we still want great exclusives, tip offs from well-cultivated contacts and brilliantly written features. We still need to be superb at the basics

Yet the opportunity to do these things has already diminished. Reporters have arranged to meet contacts only to be told they cannot afford to do so unless it results in a guaranteed story. How can contacts possibly become “well-cultivated” under those circumstances?

Even getting to these meetings has become harder now that all work-related train travel - an important consideration given the size of the patch reporters have to cover - has to go through a non-editorial manager rather than be claimed back under expenses.

Trinity Mirror wants reporters to be “superb at the basics” but, a fortnight into Newsroom 3.1, staff are already being told to make serious compromises to fundamental journalistic standards. I am told that, on July 21, a reporter was instructed by an editor to lift quotes from the website of the rival Croydon Guardian instead of corroborating the story himself. On a separate occasion another journalist was allegedly told to “cannibalise” a story from the same paper.

A source said: “[The reporter] was told by an editor to steal quotes because the policy is now to get a story up straight away if [the Guardian] ever have something we don’t. It’s embarrassing.”

That 1,000 clicks barrier

Under a section entitled What Not to Do, the guidance says reporters should focus on “what we shouldn’t be writing about” adding: “Just because someone wants us to write something doesn’t necessarily mean we should write it.”There’s nothing controversial about that; the same quality control happens in every newsroom. What is new is the way these web-only newsrooms draw the distinction between what is worth reporting and what is not.

The guidance continues: “If you don’t think a story is likely to get at least 1,000 page views then talk [to an editor] and we can make a judgment on whether we feel something should be covered. Important stories may still be covered even if we fear it might not get 1,000 page views but it may be a case of presenting or headlining them differently to how we normally have done.”

Ceri Gould said on Twitter that it was “factually incorrect” and “utter rubbish” to claim that this was her group’s policy. After being provided with an extract from the guidance, she responded:

Writing in his blog, David Higgerson, digital publishing director for Trinity Mirror regionals, also denied the policy existed before going on to justify it. He said the company wanted to start a conversation about stories that gain less than 1,000 hits. It was, he said, a case of “cold economics”: stories that do not get page views do not generate advertising revenue. He said Trinity was trying to “survive and remain relevant”.@Gareth_Davies09 'policy doc?' is news ed saying, if you want to write story few want to read please speak to me first. 'Twas ever thus— Ceri Gould Thomas (@CeriGould) July 30, 2016

Neil Benson, the company’s editorial director, said: “The point is that journalism without an audience is pointless.”

Such replies are to be expected from a company that judges the value of a story only by the number of page views it receives. Such a policy also echoes a growing problem with a media industry reliant on Facebook for generating traffic. As Kath Viner, editor of the Guardian, highlighted recently, Facebook’s news algorithms give us more of what they think we want, stories which reinforce rather challenge our existing beliefs.

Publishing content on a local news website using a crude measure of what has previously been successful plays into that and does little to encourage reporters to cover under-reported subjects.

On an average day a sizeable proportion, sometimes most, of the stories posted on the Advertiser’s website do not get more than 1,000 page views. The paper’s online readership has increased significantly in recent years and its daily targets are hit more often than not, but that is mostly down to a handful of well-read, well-written stories.

On an average day a sizeable proportion, sometimes most, of the stories posted on the Advertiser’s website do not get more than 1,000 page views. The paper’s online readership has increased significantly in recent years and its daily targets are hit more often than not, but that is mostly down to a handful of well-read, well-written stories.

Plenty of important topics, the sort of things local newspapers have a duty to report - local politics, complex health or education stories, for example - are often read by less than a thousand people. The early stories about Lillian’s Law, an Advertiser campaign which prompted a change in drug-driving legislation in England and Wales, did not exceed that number. For the Advertiser this policy will create a website dominated by crime and Crystal Palace.

Live-blogging the opening of a pub or KFC

There’s another issue, given that the newspaper is now made entirely of stories taken from the web. It means the 8,000 people who still buy the paper will stop getting certain types of news. For instance, this week’s paper had no "news in brief" columns, often made up of community stories and events. As they would not reach the page view threshold, they are now presumably seen as worthless.

Trinity Mirror's changes to their print products might be easier to stomach if they had led to significant improvements in the quality of their websites - after all, it cannot be ignored that fewer and fewer people are buying newspapers.

Certainly traffic to the company’s websites has improved since Newsroom 3.1 was introduced, and given that’s how Trinity Mirror measures success, it is unsurprising the company treats the regular criticism it receives (media commentator Roy Greenslade recently accused chief executive Simon Fox of “strangling his newspapers to death”) with incredulity.

It’s also making lots of money, helped by dreaded “synergy savings” (see cuts) after the acquisition of Local World.

Even in the relatively short period I worked for the company I noticed an improvement in how we covered breaking news - if live-blogging almost everything is a sign of progress.

Even in the relatively short period I worked for the company I noticed an improvement in how we covered breaking news - if live-blogging almost everything is a sign of progress.

During major incidents the difference is marked and, for the most part, provides a better public service. But the obsession with live-blogging extends to coverage of the opening of a Wetherspoon’s pub or a KFC.

The trivialisation of news means reporters are asked to turn almost everything into a list, as if no reader could possibly understand what they’re being told unless there’s a number in front of it. My former colleagues have been asked to liven serious stories up by “writing like they would talk down the pub”. This is the “journalism” becoming a growing feature of local and regional newspaper websites up and down the country.

The trivialisation of news means reporters are asked to turn almost everything into a list, as if no reader could possibly understand what they’re being told unless there’s a number in front of it. My former colleagues have been asked to liven serious stories up by “writing like they would talk down the pub”. This is the “journalism” becoming a growing feature of local and regional newspaper websites up and down the country.

It wasn't a bed of roses before TM took over

All of this is not to pretend that the Advertiser, and its sister papers, were problem-free before Trinity Mirror.

In 2012, then owner Northcliffe Digital moved the paper’s office to Redhill, half an hour away from Croydon. Staff, most of whom lived in London, received no adjustment to their salary to take into account having to travel ten miles away from the patch they were meant to be covering in order to get to work. Overnight the number of people visiting the office plummeted and never recovered.

When the Daily Mail and General Trust-owned company streamlined its business in 2012 in preparation for the sale to David Montgomery’s Local World, it announced that up to 38 jobs were at risk in Essex, Kent, Sussex and Surrey. Newsrooms were told the gap left by their soon-to-be-departed colleagues would be filled by a massive increase in the amount of copy provided, for free, by readers.

The company envisaged that as much as 60 per cent of its newspapers would be made up of user-generated content (UGC) and it also opened up its websites to allow people to post stories online without any editorial input. The proposals prompted several senior reporters at the Advertiser to leave but, for the most part,the company’s bleak vision of the future was never realised. After a few months it became clear that few, if any, members of the public were interested in producing these stories, especially for nothing, and most of those posted directly online were done so by police and local council press officers, who realised it was an opportunity to publish unfettered PR.

Local World arrived determined to make much-needed improvements to its new papers’ online coverage. Its solution was to tell already overstretched and undermanned news teams they had to produce twenty times more stories without any extra resources. The company even got rid of each paper's digital publishers. The pressure to meet targets was so great that some editors plumbed incredible new depths. One sent a photographer to the local high street to snap people secretly, then published the gallery online to a swath of complaints. Another wrote stories about nude celebrities and even published a map of all the dogging sites in the county. One paper has a reputation for outright fabrication of football transfer stories for clubs not even on its patch.

The Advertiser was fortunate in it had a good crop of reporters, covered a newsy patch and, critically, had an editor who did his best to shield the paper from this clickbait culture. The importance of being led by the right person should not be underestimated. Our editor eventually left with no permanent job to go to when he was told by his Local World bosses that crime was going to be barred from the front page of the paper following complaints from commercial managers. The company would later replace a journalist of 45 years’ experience with two part-time reporters tasked with writing lists for the website.

Similar issues have affected local and regional newspapers up and down the country. Some, including some owned by Trinity Mirror, have been closed or become online-only. While taken individually, these problems might seem inconsequential, the end result has been to create an industry that, as a whole, is unable to adequately fulfil the role of local journalism - to provide a public service, to be a vital part of democratic accountability, to be a force for change for causes that would otherwise go unnoticed and to chart social history. There’s no easy answer, though the ownership model of citizen publications such as The Bristol Cable provides a potential hint by removing local media from the control of large companies. But the solution cannot be to turn newspapers, and their associated websites, into thrown together collections of clickbait.

No comment from TM - but the door is still open

I approached Trinity Mirror for comment on the issues above and was told by a press officer that none would provided unless I identified where the article would be published. Since I cannot see what bearing that would have on the answers, I did not provide that information. Neil Benson, the company’s regional editorial director, did send a lengthy statement to Press Gazette, which included the thinly veiled suggestion that I left because I wasn’t “up” for the pace of live-blogging (I reported from the middle of a riot, including after being beaten up, for ten hours). He said the company was “disappointed” and “baffled” by my “outburst”- a not insignificant part of the problem - and that since the new structure had been introduced, the “culture” at the Croydon Advertiser “has been one of positivity and excitement about what the future has in store and how the newspaper and website are evolving”.

Having read this article, I’ll leave you to decide.

Benson added: “As the UK’s largest publisher, nobody cares more about the success of the local media industry than Trinity Mirror and nobody has more of an interest in the local media industry succeeding than Trinity Mirror. The changes we make are about exactly that, ensuring there is a future for our newsbrands.”

If you are a journalist working on a local or regional paper and have experienced issues similar to those outlined in this article please contact gdavies06@googlemail.com in confidence. For those using PGP encryption, his public key is 4CEE 0B57 E05F D9C1 A9D9 E282 A7DC DA88 E58F DD92.

If you are a journalist working on a local or regional paper and have experienced issues similar to those outlined in this article please contact gdavies06@googlemail.com in confidence. For those using PGP encryption, his public key is 4CEE 0B57 E05F D9C1 A9D9 E282 A7DC DA88 E58F DD92.